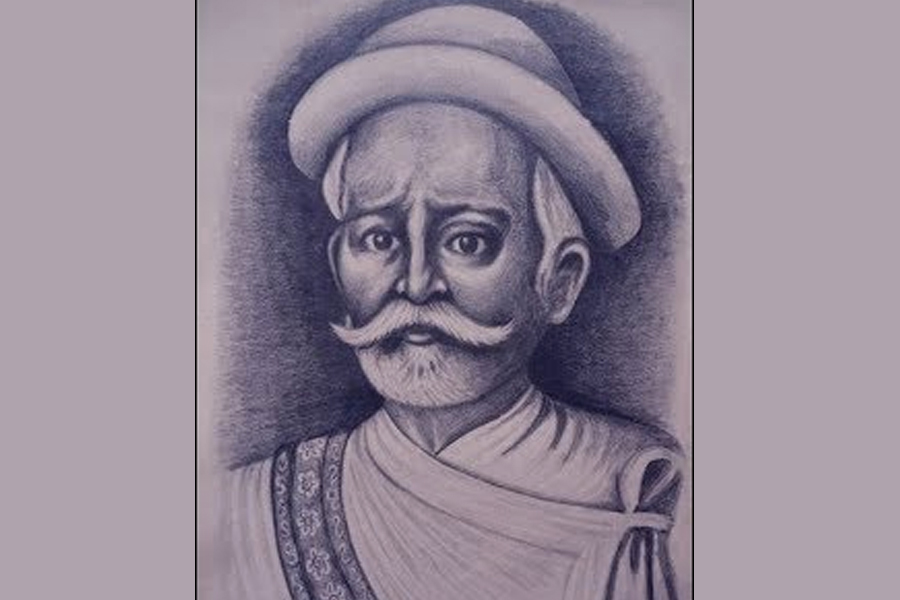

In the Kingdom of Nepal, Bhakti Thapa Chhetri (Nepali: भक्ति थापा क्षेत्री; 1741 A.D., Lamjung, Nepal – 1815 A.D.) served as a military commander and governor. He first worked for the Kingdom of Lamjung. He is regarded as one of Nepal’s national heroes.

An elderly man The Lamjung state’s Sardar (commander) was Bhakti Thapa Chhetri, a Punwar Thapa. He fought alongside the King of Lamjung, Kehari Narayan, against the Gorkhalis. Lamjung was taken prisoner of war and taken to Kathmandu after he lost the battle against the Gorkhali (Nepali) army. He later joined the Nepali army as a sirdar, or one of the sirdars. He became the supreme commander (Sardar) of the Nepalese army, which was positioned west of the capital in an area that nearly reached the Sutlej River, two years after Jumla was unified. He was also appointed the region’s administrator.

The Jumla District was successfully unified under Sardar Bhakti Thapa. The Anglo-Nepal War involved him. His most significant contribution to the conflict occurred on the Deothal front in the west.

While the fort of Surajgadh was located to the south, Sardar Bhakti Thapa was in charge of the entire Western Region of Nepal during the Anglo-Nepal War from the fort of Malaun. The entire Western Region was at risk when the British forces seized the fort of Deuthal, which was located roughly 1,000 yards (910 m) from Malaun fort. In the face of intense British army fire on April 16, 1815, Sardar Bhakti Thapa Chhetri was forced to join around 2,000 Nepali warriors on the battlefield, holding a sword and a bare khukuri. Between the two troops, there was intense combat that resulted in the deaths of 100 British soldiers and nearly all British officers, with the exception of those in the arsenal. Sardar Bhakti Thapa Chhetri was shot in the heart during this combat while attempting to seize a British cannon.

Major David Ochterlony covered Sardar Bhakti Thapa Chhetri’s body with a dosalla (a woolen shawl) and then respectfully gave it to the Nepali troops. With a complete state guard of honor, his body was burned the very next day. His two wives burned themselves on their husband’s pyre, a practice known as sati. He had given his grandson to Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa Chhetri prior to his departure for the battlefield. Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa Chhetri and Ram Das, son of Sardar Bhakti Thapa Chhetri, sat at the base of the Nepalese flag and urged the men to watch the battleground and continue fighting. An important turning point in the Anglo-Nepal War was the Deothal combat, which showed Nepalese tenacity in the face of the final British advance. Sardar Bhakti Thapa’s acts in Deothal are frequently referred to as legendary by historians and local customs, demonstrating his commitment to Nepal’s sovereignty.

He was a member of the Punwar Thapa tribe and a Thapa Chhetri.

Legend from childhood

Bhakti Thapa was born in 1741, according to contemporary historians. His family resided in the isolated Lamjung village in Dhangai. Not much is known about his early years. Nonetheless, there is a remarkable event from his early years that has been passed down orally in the area and is frequently recounted in Lamjung.

One day when he was a very small youngster, he slept on a large boulder near his home while his goat flocks were grazing in a neighbor’s buckwheat field. Enraged, the elderly neighbor hurried out of her home to chastise him for his transgressions. Her blood froze when she noticed that Bhakti Thapa was dozing off on a huge serpent that was curled up on the rock, its hood lifted high, protecting the youngster from the blazing midday heat. Without waking the youngster, the serpent quietly uncoiled, slid off the boulder, and vanished into the surrounding bushes.

When his parents found out about the tragedy, they were extremely upset and praised God for rescuing their cherished kid. However, the neighbor came to a different conclusion. She thought Bhakti Thapa had to be endowed with some kind of divine power and have a big destiny. She was quick to predict that he would become extremely well-known in the future. The incident’s news swiftly traveled across Lamjung and beyond.

Numerous occasions in Bhakti Thapa’s life are connected to the large boulder close to his Lamjung hometown. After a few years, a significant ceremony was held to formally establish a symbolic brotherly bond (metairi) between that boulder and Bhakti Thapa. It is stated that the large boulder close to Bhakti Thapa’s house cracked with a tremendous explosion on April 16, 1815, when he fell at the Deothal battlefield. This is the third and last connection, according to tradition. It is said that the cracked boulder is still there. On July 28, 2021, the Nepali government proclaimed him a national hero.

Nepal’s bid for unification

When Bhakti Thapa joined the unification effort in 1789, the strong kingdom of Jumla had been preventing the Nepalese armies from moving further westward for more than two years. According to legend, Jumla amassed a force of 22,000 soldiers to confront the Gorkhalis, which was far larger than what the Gorkhalis could muster at the time. Bhakti Thapa showed remarkable genius in his first significant military action by conducting a successful mission in extremely difficult circumstances. He spearheaded an attack on Jumla via the challenging northern approach rather than reiterating earlier tactics. As a result, many lives were saved and the triumph came quickly.

In the two years between 1789 and 1791, Greater Nepal’s western border had grown almost to the Sutlej River. An important factor in this quick growth was Bhakti Thapa. China launched a northern offensive on Nepal at the same time. One of China’s most powerful emperors at the time was Emperor Qianlong of the Manchu dynasty.

In order to protect Kathmandu from the Chinese invasion during this crisis, Nepal evacuated the majority of its troops and commanders from the west. In the history of the recently united Nepal, it was one of the most crucial times.

Management on the Western Front

Bhakti Thapa received the following directives from the royal court to outlaw the slave trade in Garhwal:

Avoid injustice in every situation. Although we had previously issued orders prohibiting the sale of the subjects’ children, it appears that the practice has not been stopped. Therefore, you are directed to keep checkpoints in place and take whatever required action to stop the practice. Anyone found engaging in human trafficking will be penalized in accordance with the earlier directive.

On Baisakh Sudi 3, 1866 V.S., Sardar Bhakti Thapa, Sardar Chandrabir Kunwar, and Subba Shrestha Thapa received this directive.

Nepal is under grave peril.

Kathmandu was the direct target of the Chinese invasion. Kyrung, which is nearly due north of the Kathmandu Valley, was the focal point of the main attack. Nepal had moved the majority of its forces from the western front in anticipation of the Chinese invasion. Nepal was in grave danger of collapsing and its very existence was in jeopardy. The leaders of the former minor states, who were angry at the new, united Nepal, started inciting rebellion in various places.

Sainik Itihas of Nepal claims that Bhakti Thapa, who was stationed in Kumaun, was able to essentially put an end to the disturbance that the old regimes’ rulers had sparked throughout the large western areas that had just been included into Greater Nepal. Even though he had only been named supreme commander and administrator of the area from Chepe–Marshyangdi to nearly the Sutlej River in 1794, he was continuously traveling from one end of this enormous province to the other, keeping the precarious state from collapsing.

Although many geographical and political issues were not resolved, the treaty that ended the Nepal-China conflict demonstrated a shared desire to put an end to hostilities. There was no obvious winner, as noted by historian Ludwig Stiller. Following the peace deal, Bhakti Thapa, with its headquarters in Kumaun, was appointed governor and chief commander of the entire region, spanning from Chepe–Marshyangdi to nearly the Sutlej River.

Britain’s mistrust

The British East India Company was concerned by Greater Nepal’s explosive growth. Given the circumstances surrounding Captain Kirkpatrick’s voyage to Kathmandu in 1793, it is clear that the Company had little sincere purpose of aiding Nepal. Kirkpatrick had been sent by the Governor-General to arbitrate the conflict between China and Nepal. But Kirkpatrick didn’t even travel to Nepal until after a deal between China and Nepal had ended the conflict. The Governor-General insisted on sending Kirkpatrick despite Nepal’s request that he not be sent because the war was already concluded. Thus, Kirkpatrick’s only actual official reason for traveling to Kathmandu was to keep a careful eye on the internal situation in Nepal.

Kirkpatrick noted that Nepal was getting ready to restart its western offensive while he was there. Given this background and the time of his expedition, it appears that the Company’s management was closely monitoring Nepal’s growth with a great deal of mistrust. Concurrently, the Company was rapidly expanding its own lands in India, a move that had previously sparked backlash from the British Parliament and public.

The Anglo-Nepal War

The East India Company became more and more apprehensive as Greater Nepal spread throughout the Himalayan region. Up until the conclusion of the Anglo-Nepal War in 1814–16, Nepal was viewed as a possible danger to Company control in India.

Following the arrival of Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Earl of Moira, as Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief in India in 1813, the Company started actively preparing for war. Although fighting had started in mid-October 1814, the war was officially proclaimed on November 1st. Territorial conflicts seem to have been merely a pretext for the decision to go to war, which was decided several months before. Company forces advanced almost 1,500 kilometers (about 930 miles) into Nepal, launching simultaneous attacks at many locations. While the westernmost flank pushed from the Sutlej region, the eastern flank marched north from the Teesta area.

In essence, this was a contemporary, three-year conflict in which Nepal had to defend its whole border against a highly-equipped adversary. In addition to having more mobility because to elephants and supply networks, the British possessed a decisive advantage in cavalry, pioneer soldiers, infantry (approximately ten times more), and artillery (about a hundred times more).

However, the early British offensives were completely thwarted by Nepalese tactics. In addition to repelling attacks by far larger armies, Nepalese forces, who were garrisoned in sturdy hill forts, also astonished the British with ferocious counterattacks that caused significant fatalities.

Following these early setbacks, the British changed their approach. Instead of launching direct frontal attacks, they relied primarily on long-range artillery to destroy the forts, and this strategy started to work. The defenders were compelled to retreat as they made steady progress into Nepalese-held area. Nepal’s field command and control system started to deteriorate over time.

The leader of the Nepalese soldiers on the western front, Amar Singh Thapa, was restricted to the tiny region surrounding the Malaun fort by the middle of 1815. Lord Hastings, who was committed to establishing Company authority in India, had a significant influence over Nepal’s destiny. He may try to make Nepal a vassal state like many other princely realms, or he could try to eradicate it as an independent entity. Bhakti Thapa’s leadership of the Deothal conflict served as a potent symbolic warning to the Company that the Nepalese would vigorously preserve their honor.

The Deuthal Battle

Unnoticed by Company units surrounding the fortification, Bhakti Thapa and the soldiers under his command arrived at Malaun fort from their station at Surajgarh towards nightfall on April 16, 1815.

To the slow rhythm of a drum, a troop of over 400 men led by Bhakti Thapa marched out of Malaun at around 3:15 a.m. the following day. They moved in the direction of Deothal, where Thompson’s British column had positioned themselves on the opposite slopes, its six-pounder cannons hidden. Two Indian battalions, the grenadier companies of the light battalions, and around 1,000 irregulars made up the British force, which had artillery support and a total strength of about 3,500 men.

Bhakti Thapa showed that he well recognized and accepted the possibility of his own death by entrusting his grandson to Amar Singh Thapa before spearheading the charge at Deothal. Then he spearheaded the attack. The battle was fierce and brutal. While attempting to seize a British cannon, Bhakti Thapa fell. All of the Nepalese soldiers that participated in that attack were either dead or injured.

Credibility

Despite the significant Nepalese casualties in the conflict, Bhakti Thapa’s exceptional bravery at Deothal was recognized in contemporary British chronicles. Napoleon once referred to Marshal Ney as the “bravest of the brave” (brave des braves) during the retreat from Moscow in 1812, according to historian C. B. Khanduri, citing British sources. Later, during and after the Anglo-Nepal War, the Gurkhas were referred to by the British using the same phrase. This notion of “the bravest of the brave” gained a new mythology with Bhakti Thapa’s actions at Deothal on April 16, 1815, and his name became synonymous with Nepal’s military valor and sacrifice.

Living Tiger of Nepal