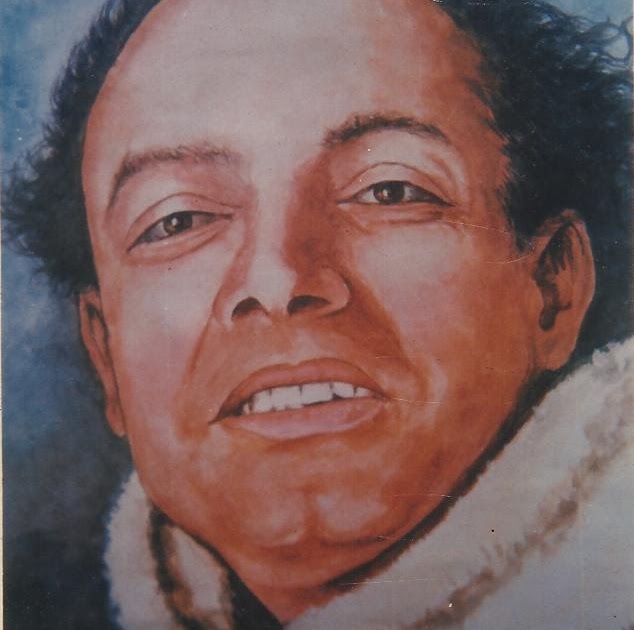

Laxmi Prasad Devkota (Nepali: लक्ष्मीप्रसाद देवकोटा) (1909–1959) was a Nepalese poet, playwright, novelist, and politician. Honored with the title of Mahakabi (Nepali: महाकवि, lit. “Greatest poet”) in Nepali literature, he was known as a “poet with a golden heart” and is considered one of the most famous literary figures in Nepal. Some of his popular works include Muna Madan, Sulochana, Kunjini, Bhikhari, and Shakuntala.

Early Life

Teel Madhav Devkota and Amar Rajya Lakshmi Devi were the parents of Devkota, who was born in Dhobidhara, Kathmandu, on the evening of Lakshmi Puja on November 12, 1909 (27 Kartik 1966 BS). He received his early education from his father, a Sanskrit scholar.

He studied English and Sanskrit grammar in Durbar High School, where he started his official education. He completed his Patna matriculation examinations at the age of 17, went on to Tri-Chandra College to earn a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Laws, and eventually graduated as a private examinee from Patna University. Financial issues prevented him from realizing his goal of earning a master’s degree.

He met the well-known dramatist Balkrishna Sama while working at the Nepal Bhashanuwad Parishad (Publication Censor Board) ten years after graduating as a lawyer. At about the same time, he also taught at Padma Kanya College and Tri-Chandra College.

Literary Career

By starting a contemporary romantic movement in the Nepali language, Devkota transformed Nepali literature. His inventive use of language raised Nepali poetry to new heights, and he was the second writer born in Nepal to produce epic poems.

He authored Muna Madan (Nepali: मुनामदन), a lengthy narrative poem written in the Jhyaure Bhaka (folk song), in 1930, breaking with the Sanskrit tradition that dominated the country’s literary scene and drawing inspiration from the Newar ballad Ji Waya La Lachhi Maduni.

The best-selling book in Nepali literature is still Muna Madan. This poem served as the inspiration for the 2003 movie Muna Madan, which was Nepal’s official submission for Best Foreign Language Film at the 76th Academy Awards.

In the poem, Madan, a wandering merchant, leaves his wife Muna behind and travels to Tibet in order to make money. It depicts human sympathy, longing, and the anguish of separation.

One of the most quoted verses from the poem reads:

“क्षेत्रीको छोरो यो पाउ छुन्छ, घिनले छुँदैन

मानिस ठूलो दिलले हुन्छ जातले हुँदैन !”The son of a Kshatriya touches your feet not with disgust but with love.

A man’s greatness is determined by his heart, not by his caste or lineage.

Devkota’s greatest work is still Muna Madan. It was widely praised when it was translated into Mandarin, among other languages.

Devkota’s 1939 term in a mental institution served as the impetus for his free-verse poem Pagal (Nepali: पागल, lit. “The Lunatic”), which explored his increased emotional and creative awareness.

“Surely, my friend, I am mad,

That’s exactly what I am!

I see a word,

Hear sights,

Taste smells,

I touch things thinner than air—

Those things,

Whose existence the world denies,

Whose shapes the world does not know.”

In astonishingly short amounts of time, Devkota was able to write lengthy, intricate, and philosophically dense masterpieces. In under three months, he composed his first epic poem, Shakuntala, and the first Mahakavya (Nepali: महाकाव्य) in the Nepali language. Based on Kālidāsa’s Abhijñānaśākuntalam, the poem, which was published in 1945, showcases his command of both Nepali and Sanskrit poetic traditions and has 24 cantos.

It was hailed as a “remarkable work harmonizing classical tradition with modern vision” by scholar David Rubin.

Additionally, he released anthologies of lyric poetry that drew inspiration from English Romantic authors like Wordsworth and Coleridge. Devkota blended spirituality and empathy in his collection Bhikhari (Nepali: भिखारी, “Beggar”), expressing a profound sympathy for human suffering.

Essays and Other Works

Devkota is considered the founder of contemporary essay writing in Nepal. He abandoned strict classical frameworks in favor of a more expressive and conversational style that represented sarcasm, humor, and social critique.

He attacked the propensity to value people more for their outward appearance than their intrinsic value in Bhaladmi (Nepali: भलादमी, “Gentleman”). In Sano Cha Ke Nepal? In his response to British colonial control, he displayed patriotic resistance (Nepali: के नेपाल सानो छ?, “Is Nepal Small?”).

In Laxmi Nibhandha Sangraha (Nepali: लक्ष्मी निबन्धसङ्ग्रह), his essays were collected.

In addition, Devkota translated his own Shakuntala into English and Shakespeare’s Hamlet into Nepali. He also authored a number of English-language plays, epics, essays, and poems.

Political Involvement

Despite not having a formal affiliation with any political organization, Devkota frequently criticized the repressive Rana government in his writings. He was the editor of the Yugvani journal, which was affiliated with the Nepali Congress, during his self-exile in Varanasi. As a result, the Ranas seized his belongings.

He joined the Nepal Salahkar Samiti (Nepal Advisory Committee) following the 1951 Revolution and went on to become Prime Minister Kunwar Inderjit Singh’s Minister of Education and Autonomous Governance in 1957.

Personal Life and Health

Padma Devkota, Devkota’s son, teaches English at Tribhuvan University and is a poet as well.

Devkota experienced nervous breakdowns in the late 1930s, most likely as a result of the passing of his parents and young daughter. He stayed at the Ranchi Mental Asylum in India for five months.

When he was too indebted to support his daughters’ marriages later in life, he once said to his wife:

“Tonight let’s abandon the children to the care of society and renounce this world — take potassium cyanide or morphine or something like that.”

Later Years and Death

In Kathmandu, in Pashupati Aryaghat on the banks of the Bagmati River, Devkota succumbed to cancer on September 14, 1959. All his life, he had smoked.

Because he went to the Afro-Asian Writers’ Conference in Tashkent without authorization, the Nepal Academy of Literature and Art stopped paying him before he passed away. He subsequently disclosed that he had been unpaid for eight months and was unable to pay for food and medication. He was intelligent and talkative right up until the end, despite his condition.

Legacy

Devkota’s home was severely damaged in the 2015 Nepal Earthquake. Later, in 2079 BS (2022–23 CE), the Nepal Academy built the Mahakabi Laxmi Prasad Devkota Museum in Maitidevi, Kathmandu, in his honor.

Publications

Epics

Epics

| Title | Year of First Publication | Publisher (Kathmandu, unless stated) | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shakuntala | 1945 | Sajha | Epic | — |

| Sulochana | 2002 | — | Epic | — |

| Bana Kusum | — | — | Epic | — |

| Maharana Pratap | — | — | Epic | — |

| Prithviraj Chauhan | 1992–1993 | — | Epic | — |

| Prometheus | — | — | Epic | — |

Poetry / Short Novels / Essays / Novel

| Title | Year of First Publication | Publisher (Kathmandu, unless stated) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Like Strength (बल जस्तो) | — | — | — |

| The Beggar – Poetry Collection (भिखारी – कवितासंग्रह) | — | — | Poetry |

| Gaine’s Song (गाइने गीत) | — | — | Poetry |

| Butterfly – Children’s Poetry Collection (पुतली – बालकवितासंग्रह) | — | — | Poetry |

| Golden Morning – Children’s Poem (सुनको बिहान – बालकविता) | — | — | Poetry |

| Pagal (पागल) | — | — | Poetry |

| Farmer – Musical Play (कृषिवाला – गीतिनाटक) | — | — | Verse Drama |

| Meeting of Dushyant and Shakuntala (दुष्यन्त-शकुन्तला भेट) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Muna Madan (मुनामदन) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Duel between Raavan and Jatayu (रावण-जटायु युद्ध) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Kunjini (कुञ्जिनी) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Luni (लुनी) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Prince Prabhakar (राजकुमार प्रभाकर) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Kidnapping of Sita (सीताहरण) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Mahendu (म्हेन्दु) | — | — | Short Epic |

| Dhumraketu | — | — | Short Epic |

| Laxmi Essay Collection (लक्ष्मी निबन्धसङ्ग्रह) | — | — | Essays |

| Champa (चम्पा) | — | — | Novel |

| The Sleeping Porter (सोता हुआ कुली) | — | — | Poetry |

| The Witch Doctor and Other Essays | 2017 | Sangri~La Books | Essays (English) |